“My daughter, when you go on the white man’s journey, they will see their safety as your only worth. They will catalog and collect. They will name the Sacred places,” says Old Woman (Woman Who Has Always Lived) in “The Lost Journals of Sacajewea” by Debra Magpie Earling.

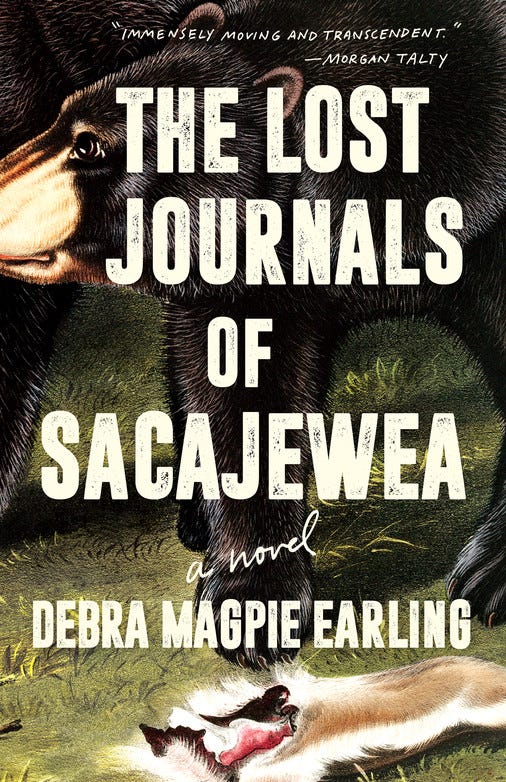

Earling’s novel, released in May on Milkweed Editions, rewrites the narrative of the Lehmi Shoshone woman known as Sacajewea in an account of her life from her imagined journals. Earling, who also wrote “Perma Red,” began the immensely moving novel as an artist book during the bicentennial of the Lewis and Clark expedition in 2004. A former professor, Earling recently retired from the University of Montana, where she was named professor emeritus in 2021. She is Bitterroot Salish.

When composing the book, Earling embodied the spirit of Sacajewea, as very little is documented of her — there are no photos, though her likeness has been imagined by many artists. Her name and its spelling are contested, and her tribal identity is claimed by several Nations. Even her age at time of capture, date and place of her death, and her role in the famed Lewis and Clark expedition is not certain.

Cast by historical accounts as a willing participant in the travels of Merriweather Lewis and William Clark, Sacajewea was part of the Corps of Discovery expedition to explore land obtained by the U.S. in the Louisiana Purchase. Land that was occupied by numerous tribal nations in which the United States government planned to take by treaty or by force.

Lewis and Clark were tasked with finding the headwaters of the Missouri River, and Sacajewea knew the way to the Three Forks, where the rivers become one. She would recognize the land from where she was stolen. This was her currency — an Indigenous woman to showcase on their travels, to soften relationships, and to have a guide bring them into the wild unknown.

Sacajewea, for all the narratives that exist, is rarely portrayed as a stolen sister, a slave, a victim of rape, and a teen “bride” sold to a cruel man who found her subhuman. Earling reimagines Sacajewea’s undocumented story as one of brutality and survival, of deep connection to place that became her salvation from the territory of her captors.

“An enslaved young girl traveling with a military expedition spoils the long held notion that the expedition was wholesome,” writes Earling. “And yet, two hundred years after the Lewis and Clark Expedition the ‘historical’ Sacajewea codifies an account that does not sully the discovery narrative. She does not speak. She does not fight back in visible ways. She participates. Or does she?”

In the novel, Earling imagines the ways Sacajewea may have fought back, and her voice is threaded through journal entries she may very well have kept. As a Lemhi Shoshone, it is likely Sacajewea lived with her people in the upper Salmon River Basin in present-day Idaho. She was stolen at an undetermined young age by the Hidatsa, an enemy tribe, during a deadly raid on her village in 1800. She was taken to the area that would become North Dakota, to the Mandan and Hidatsa villages near present-day Bismarck. Along with another stolen Shoshone sister, Otter Woman, she was sold to Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian fur trader living at the camps. A rough figure by documented accounts, Charbonneau was observed raping an Ojibwe woman during a trapping expedition and being stabbed by her mother in 1795.

Charbonneau purchased Sacajewea in 1804 and impregnated her. She was perhaps 16, possibly younger. Though he is known as her husband, as well as being married to Otter Woman, their legal marriages are not documented.

Lewis and Clark arrived at the villages that same year, and the newcomers began to build Fort Mandan. They planned to continue west, cross the Rocky Mountains and eventually arrive at the Pacific Ocean that following year. They left the Dakotas in 1805, and Charbonneau brokered his passage by offering Sacajewea, who had just given birth, as an interpreter and guide.

“Long ago, the People knew Life rested in what must-not-be-named,” writes Earling. “When all things are named, when all Earth’s gifts are claimed without thanks, without stories, without prayer, Water and fire will come,” Old Woman (Woman Who Has Always Lived) tells Sacajewea. “Pray to all Four Directions. Pray to heal the desecrated path,” one that was one undertaken by expeditious men driven by conquest and a sense of superiority over the original inhabitants of the land.

Sacajawea carried her son, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau — born two months before they departed — throughout the entire journey. Toussaint Charbonneau also traveled with the Lewis and Clark expedition, where Lewis described him as “a man of no peculiar merit” and a timid waterman who also beat his wife, for which Clark intervened.

Clark became attached to Sacajewea’s child and nicknamed him “Pomp” or “Pompey.” He would eventually adopt Jean Baptiste as well as Sacajewea’s second child, Lizette Charbonneau, following her death. She may have died after her daughter was born in 1812 from putrid fever in St. Louis, where she resided with Charbonneau after the expedition ended in 1806, but by other accounts she returned to the Shoshoni and died in 1884 on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming.

Even her name was not her own but assumed to be bestowed upon her by her captors, as the Hidatsa word for bird is “sacaga” and woman is “wea.”

Lewis left just one clue about his lifesaving guide in his journals, naming “a handsome river of about fifty yards” for her in 1805. “This stream we called Sah-ca-gah-we-ah or Bird Woman's River, after our interpreter the Snake woman."

Thank you Tizz for sharing <3